Above: Domestic workers demand a separate central legislation during a protest at Jantar Mantar in Delhi in 2014 to ensure that their work gets due recognition. Photo: Anil Shakya

At an estimated 35 million, they are the single largest category of female professionals in India. Can the law and the state bring them relief from their exploitation by recognising them as workers?

~By Sucheta Dasgupta

They are paid a pittance, have no overtime, no weekly day-off and zero social security. Their work is physically demanding and often involves important responsibilities, yet they are treated with scant respect and are vulnerable to abuse and crime. Frequently at the receiving end of false allegations, they are often robbed of their livelihood on the slightest pretext. Can the law address the numerous injustices and gross inequalities faced by the domestic worker?

The Supreme Court on August 4 directed the Delhi government to register all domestic workers in its jurisdiction under the Unorganised Workers Social Security Act 2008. The government of the National Capital Territory of Delhi has been asked to file an affidavit reporting the progress of this task after three months. The order was delivered in the course of hearing a special leave petition filed in 2012 by the Shramajeevi Mahila Samiti, a Jharkhand-based NGO.

The Special Leave Petitions originated from a Delhi High Court judgment, which resulted in the rescue and rehabilitation of 256 women and children from West Bengal, employed as domestic workers in Delhi, without wages, by fake placement agencies.

REGISTRATION IMPORTANT

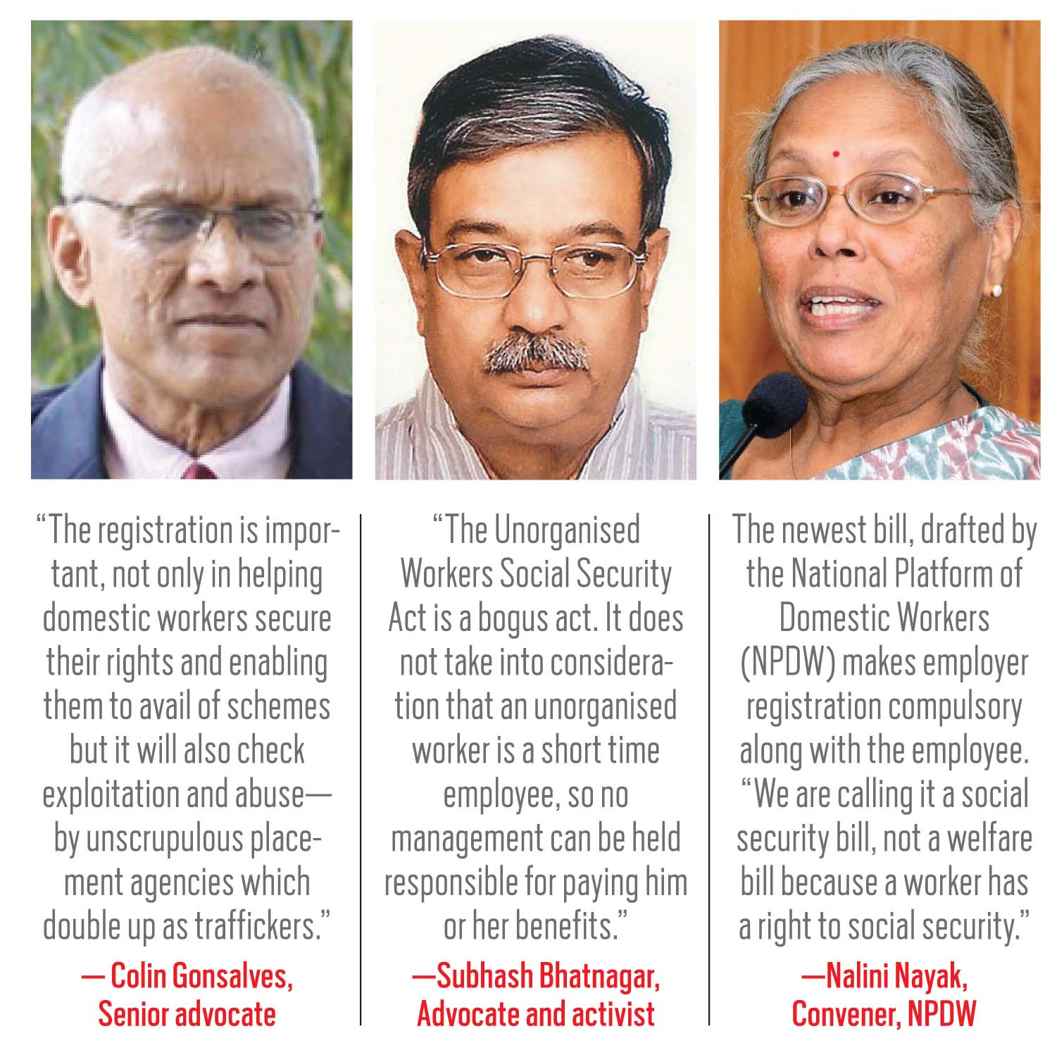

“The registration is important, not only from the point of view of helping domestic workers secure their rights and enabling them to avail the six schemes bundled under the Act, but it will also go a long way in reducing their exploitation and abuse—especially the chances of them being forced into sex work by unscrupulous placement agencies which double up as traffickers,” said senior advocate Colin Gonsalves, who fought both cases for the Samiti.

The six schemes under the Act are—Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme, National Family Benefit Scheme, Janani Suraksha Yojana, Janshree Bima Yojana, Aam Aadmi Bima Yojana and Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana. Interestingly, as Gonsalves highlights, not a single domestic worker has enjoyed the benefit of any of these schemes as no worker in the country was ever registered under the Act.

According to Census 2001, there are over six million domestic workers in India. But trade unions put this number at 35 million. Of them, 80 percent are women, making them the single largest category of female professionals in the country. What’s more, given our cultural mores which lead to unequal division of labour in the home space, they are also the enablers.

Speaking to India Legal, Nagendra Sharma, media advisor to Delhi Chief Minister, Arvind Kejriwal welcomed the SC order. “The government will begin work on the registrations soon,” he said. Asked why the registrations were not done earlier as the Act itself is nine-years-old and the government has been in power for more than two years now, he avoided a direct response but informed this correspondent that a special committee to suggest welfare measures for domestic workers had been constituted under deputy speaker Bandana Kumari in June 2015 which had submitted a report to then state labour minister Gopal Rai in October.

Among other measures, the committee sought fixing of minimum wages for the workers as per the Minimum Wages Act and punitive measures for defaulting employers.

GENDER PAY GAP

Sadly, only nine states have in actual fact included domestic workers in the list of beneficiaries under the Minimum Wages Act. These are Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Odisha, Jharkhand, Bihar and Maharashtra. Even so, the revised salaries are too meagre to make a difference. For instance, the pay for eight hours of domestic chores in Rajasthan has been fixed at Rs 5,642 per month by the state labour department. That’s a handsome amount; considering that workers elsewhere, including Tier I cities and the national capital, typically draw anywhere between Rs 2,000 and Rs 5,000, depending on their luck and location.

Pertinently, although they handle key duties like child care and care of the elderly, perform hard labour and significantly enhance the quality of life of their employers, domestic workers draw less than half of what is taken home by a gardener or a driver, which is typically between Rs 10,000 and Rs 12,000. As the gardener or driver is rarely female, it brings into focus another important area of rights inequality—the gender pay gap in the unorganised sector.

One other reason for this state of affairs is that domestic work has been culturally undervalued for the longest, so governments prefer to close their eyes to the issue. Hence there is no legal definition of a domestic worker. This may be what has led to India not ratifying the International Labour Organisation’s 189th convention, or the Convention on Domestic Workers, held in 2011, despite being a signatory. Domestic workers are still referred to and viewed as “help” or, euphemistically, “housemaids”, which is what unmarried and homebound daughters were called in the Victorian era, thus depriving them of a legal definition.

Money, influence and class are also a factor. We may be implementing flexi-time and opting for home offices in the white collar corporate milieu, and debating wages for male and female homemakers, but we are reluctant to regulate this huge enterprise because it falls in the unorganised sector.

Thus, despite the Law Commission recommending it in 2015, the Maternity Benefits Act 2017, which gives 26 weeks paid leave to women in the organised sector, has excluded unorganised workers. They may only avail relevant schemes under the Unorganised Workers Social Security Act provided they are registered therein, which means they stand to lose income when they decide to expand their families and become mothers.

BOGUS ACT

“The Unorganised Workers Social Security Act is a bogus act. It does not take into consideration the fact that an unorganised worker is a short time employee, so no management can be held responsible for paying him or her benefits. It does not address the problem of funds. What is needed is a permanent set up which can have an account in the bank and money. Nothing like that was provided in the 2008 Act,” Subhash Bhatnagar, advocate and activist, told India Legal.

Indeed, the Act is a very sketchy one, full of loopholes, leaving several immediate critical concerns unattended. The Act states that the government shall formulate and notify, from time to time, suitable welfare schemes for unorganised workers on matters related to life and disability cover, health and maternity, old age benefit, employment injury benefit, employee skill upgradation, even provident fund and housing. The list is long and ambitious. But all one is left with is a handful of schemes, which are hardly exhaustive and the procedure to enlist for which is ambiguous and involves references and verifications, leading to corruption with fake beneficiaries finding their way into the lists and cornering the nominal insurance money and paltry pensions.

Another grey area left untouched is where the domestic worker should go in case of any disagreement with the employer as the labour court only serves organised workers. As a rule, the labour ministry never engages with the informal sector, citing lack of manpower. To solve this problem, say activists, it is imperative that the government legislate to bring domestic workers under Schedule I of the Employment Act. The labour department must also put more people in place to mediate and settle the countless cases of daily disagreements between employers and domestic workers within a specific time frame.

It has been found that the National Social Security Board, as envisaged in Section 5 of the Act, was first constituted in 2009, reconstituted in 2013, and its term was over in 2016. The Supreme Court bench of justices Kurian Joseph and R Banumathi has directed its reconstitution within a month.

In the last one year, three private member’s bills have been introduced in parliament. In August 2016, Congress MP Shashi Tharoor introduced the Domestic Workers’ Welfare Bill, 2016 in the Lok Sabha. This April, Oscar Fernandes of the Congress placed the Domestic Workers (Regulation of Work and Social Security) Bill in the Rajya Sabha. And in July, CPI(M)’s Sankar Prasad Datta placed an updated version of the same bill for the consideration of the Lok Sabha. The bill has also been submitted by MP Jitendra Choudhury to the petitions committee of the Lok Sabha. The committee has admitted the petition.

However, a private member’s bill is one that does not have the backing of the party the parliamentarian represents. Hence only one private member’s bill, the Rights of Transgender Persons Bill, has been passed in the last 47 years. Nevertheless, the newest bill, drafted by the National Platform of Domestic Workers (NPDW), may be seen as an exercise in awareness-building.

It has two important points of departure from the 2008 Act—it makes employer registration compulsory along with the employee and makes the employer responsible for paying an annual fee for the registration which will go into funding the social security for the employee and will be equivalent to their one month’s salary, thus establishing a mandatory employer-employee-government tripartite relationship, and it also takes care of the rights of the live-in worker.

According to the provisions of the bill, a live-in worker, as distinguished from a full-time worker who invests only eight hours every day in work, is entitled to overtime pay over and above 12 hours of work, a weekly off during which she is not on call and is free to travel anywhere within or outside town and an annual leave. This, Bhatnagar said, is crucial as it is the live-in workers who suffer the most when they leave their children and spouses behind to work for their employer, giving up the pleasures of family life.

The bill also plans for upgrading the skills of such workers so that after a certain time, the worker may take up work that allows them to live with their families. Employers who default on registration and contribution or are found denying their employees their rights are liable to be punished with a prison term of three to six months, or a fine of Rs 20,000 to Rs 40,000, or both.

These are all ideas which can be fruitfully explored. As Nalini Nayak, convener, NPDW, put it: “We are calling it a social security bill, not a welfare bill because a worker has a right to social security.” Dr Sister Lissy Joseph added: “The middle class has to join the working class to protect our fundamental rights, otherwise it will be too late.”

The NPDW seems to be on the right track…