The print and visual media have shored up a raging controversy over the killing of eight Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI) fugitives, who escaped from the Bhopal Jail on the night of October 31, killing a guard while doing so. Within eight hours of their escape, they were accosted by the villagers, resulting in altercation and stone-pelting. The villagers informed the local police, who had immediately stepped in. The police were already on the hunt for the fugitives. When the escapees tried to slip away, the police opened fire resulting in the death of all the eight. These are the broad undisputed facts.

A section of liberal media and rights activists have questioned the propriety of the police action and termed it as a fake encounter and violation of human rights. Some video footages and voice records have been pressed into service to prove their point that the eight were unarmed. They say that multiple bullet injuries found on the upper portion of the body of each of the deceased suggest a deliberate act of killing. They have been truculently calling for action against the police personnel besides casting aspersions on the Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan and other high rank police officers of plotting to eliminate the fugitives who had jumped the legal process of fair-trial. There is also innuendo that loop holes were discreetly contrived to tempt the terror accused to escape, and then use the opportunity to kill them.

The other section of public opinion and media holds a counter-view. It condemned the liberals for shedding tears for hardened terrorists who escaped from the jail after dastardly killing of a jail officer. A section of police put forth the version that the fugitives were wielding country-made revolvers, and therefore they had to open fire in retaliation.

The visual media virtually pits the debate as human rights versus national interest. The liberals and rights activists argue that the accused are to be deemed innocent until the courts convict them. The deliberate killing of unarmed fugitives in a fake encounter is a blatant act of murder, they say. The counter-argument is that the encounter was genuine. There was no way out except killing of the fugitives. Otherwise the terror accused would have indulged in macabre acts of bomb blasts endangering lives of innocent people and exposing public property to wanton destruction because the accused they had previous history of causing bomb blasts at Ahmedabad, Pune, etc., and they had also indulged in acts of docity.

A dispassionate forensic examination of the entire episode needs to be done, devoid of a prejudiced mindset. In the context of the facts, to consider the incident as an encounter and the plea of self-defence is not admissible because the questions whether or not the fugitives carried firearms and whether they opened fire on the police provoking them to retaliate in self-defence needs to be established beyond reasonable doubt. The plea of self-defence arises in a situation where a person (including police) is confronted to save himself or save other person or the property. The right to self-defence can be exercised within the legal frame work of sections 96 to 106 of IPC. The Apex Court has unequivocally laid down the range and limitation of the right to self-defense.

In the present case, the accused escaped from jail after killing one of the jail staff. They have also a history of escape from Khandva Jail and they were re-arrested after a long gap of time. The correct legal principles applicable to the situation is to be found in the provisions of Section 46 of the Code of Criminal Procedure and Section 81 of the Indian Penal Code.

In order to impress the non-legal intelligentsia, the relevant portions of the above provisions are produced here under:

CrPC 46: Section 46 of the Criminal Procedure Code

Arrest how made

- In making an arrest the police officer or other person making the same shall actually touch or confine the body of the person to be arrested, unless there be a submission to the custody by word or action. …

- If such person forcibly resists the endeavour to arrest him, or attempts to evade the arrest, such police officer or other person may use all means necessary to effect the arrest.

- Nothing in this section gives a right to cause the death of a person who is not accused of an offence punishable with death or with imprisonment for life.

The law provides for physical arrest of the accused, and if the accused cannot be apprehended physically, the combined reading of sub-section 2 & 3 enable the police to shoot and even to cause death of the fugitive if he is accused of an offence punishable with death or imprisonment for life. Even while shooting it is required on the part of police that they shoot only at non-vital parts to disable the fleeing fugitive. When the distance between the cops and fleeing fugitive is quite distant, to insist that the bullets should strike only non-vital part is a highly improbable proposition and in such a situation no mens rea can be attributed to the cops.

Six-monthly statements of all cases where deaths have occurred in police firing must be sent to NHRC by DGPs. It must be ensured that the six-monthly statements reach to NHRC by 15th day of January and July, respectively.

—Supreme Court

The Supreme Court in Criminal Appeal No.1255 of 1999 [People’s Union of Civil Liberties Vs. State of Maharashtra & Ors] has laid down detailed guidelines which the police and the State has to adhere in the case of deaths caused in police action. The relevant portion of the directions germane to the episode is extracted:

“(10) Six-monthly statements of all cases where deaths have occurred in police firing must be sent to NHRC by DGPs. It must be ensured that the six-monthly statements reach to NHRC by 15th day of January and July, respectively. The statements may be sent in the following format along with post mortem, inquest and, wherever available, the inquiry reports: (i) Date and place of occurrence. (ii) Police Station, District. (iii) Circumstances leading to deaths: (a) Self defence in encounter. (b) In the course of dispersal of unlawful assembly. (c) In the course of affecting arrest.”

The extracted guidelines disclose the three situation under which the death is caused in police action: (i) Self defence in encounter; (ii) in the course of dispersal of unlawful assembly, and (iii) in the course of effecting arrest. The case of self-defence and encounter is altogether is a different situation from the situation where death is caused in the course of effecting arrest.

A section of liberal media and rights activists have questioned the propriety of the police action and termed it as a fake encounter and violation of human rights. Some video footages and voice records have been pressed into service to prove their point that the eight were unarmed.

In the episode under scrutiny, the fugitives with a history of causing several bomb blasts, committing dacoity and earlier having successfully escaped from Khandva jail were running at a considerable distance. The cops had no other alternative other than to shoot the fugitives who in fact a few hours before the incident had killed the jail staff before they successfully escaped from the jail. In the context of the given facts and the framework of law, the cops cannot be found to have crossed the bounds of law.

The second justification for the shootout is to be found in Section 81 in The Indian Penal Code which reads thus:

- Act likely to cause harm, but done without criminal intent, and to prevent other harm.—Nothing is an offence merely by reason of its being done with the knowledge that it is likely to cause harm, if it be done without any criminal intention to cause harm, and in good faith for the purpose of preventing or avoiding other harm to person or property.

Explanation.—It is question of fact in such a case whether the harm to be prevented or avoided was of such a nature and so imminent as to justify or excuse the risk of doing the act with the knowledge that it was likely to cause harm. Illustrations:

(a) A, the captain of a steam vessel, suddenly and without any fault or negligence on his part, finds himself in such a position that, before he can stop his vessel, he must inevitably run down to boat B, with twenty or thirty passengers on board, unless he changes the course of his vessel, and that, by changing his course, he must incur risk of running down a boat C with only two passengers on board, which he may possibly clear. Here, if A alters his course without any intention to run down the boat C and in good faith for the purpose of avoiding the danger to the passengers in the boat B, he is not guilty of an offence, though he may run down the boat C by doing an act which he knew was likely to cause that effect, if it be found as a matter of fact that the danger which he intended to avoid was such as to excuse him in incurring the risk of running down the boat C.

The illustration (a) suggests that when a person is confronted with a choice of saving a life of many as against few without any criminal intent if he elects the first choice and causes death of few his action attracts the general exception hence does not constitute any offence, much less the offence punishable under section 302 IPC.

The illustration is only a suggestive example to convey the meaning of section 81 but the illustration is not comprehensive to control and limit the wider amplitude of the purport and content of section 81 which may apply to other situations also apart from the situation stated in the explanation. A question might arise whether the lesser harm and greater harm envisaged in Section 81 should exist simultaneously and immediately for election of the choice or whether the greater harm is foreseeable one to occur indisputably after some gap and at later point of time. This proposition is Res Integra. It is necessary and desirable to accept the later interpretation in the context when the fugitive terrorist is fleeing and if they cannot be physically apprehended causing their death by shooting should be justified in law as an act done to prevent greater harm to the society at large.

In the present case the SIMI fugitives said to have history of being inspired and links with forces like Pakistan’s ISI (Inter Services Intelligence), Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Hizb-ul-Mujahidin (HuM), Al-Qaida and ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) are let loose, it would have been a ghastly risk to the innocent public. Therefore the shootout was inevitable to prevent greater harm to the public at large.

In the present case the SIMI fugitives said to have history of being inspired and links with forces like Pakistan’s ISI (Inter Services Intelligence), Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Hizb-ul-Mujahidin (HuM), Al-Qaida and ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) are let loose, it would have been a ghastly risk to the innocent public. Therefore the shootout was inevitable to prevent greater harm to the public at large. The liberals and the human rights activitists should rivet their concern and sympathy for the victims of terrorist activities rather than shedding tears for the SIMI fugitives whose deaths have been caused in a legally justifiable police action.

—The author is former Acting Chief Justice, Gauhati High Court

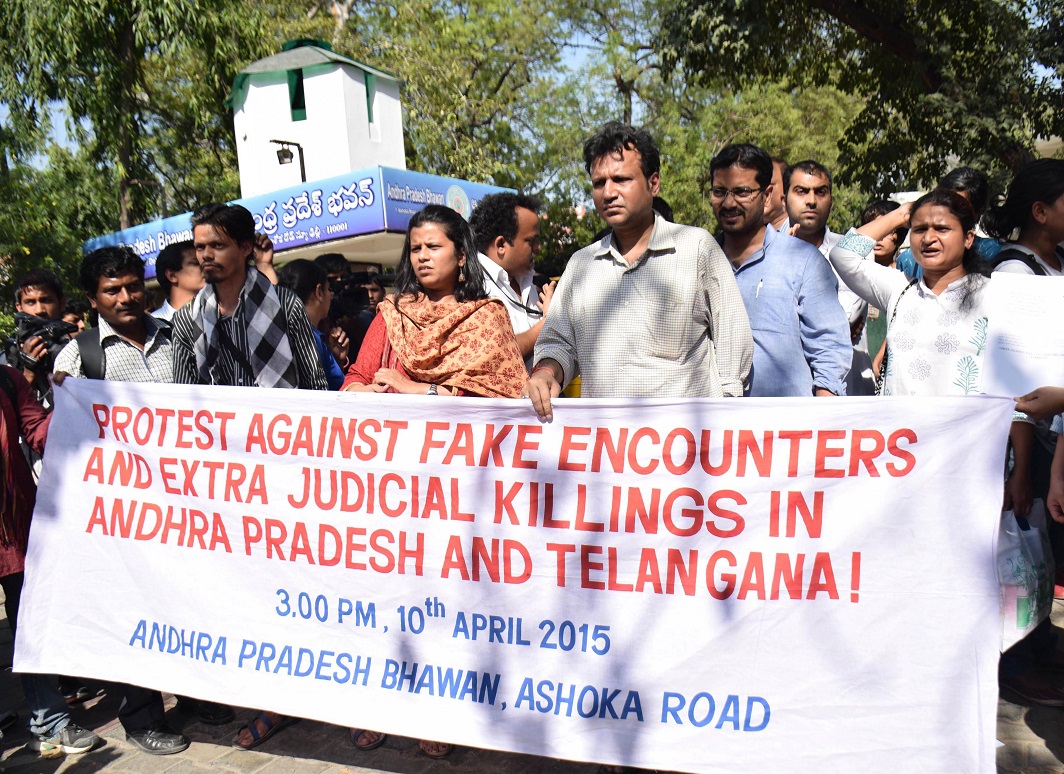

Lead picture: Police officers and Special Task Force soldiers stand beside dead bodies of the suspected members of the banned Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI), who escaped the high security jail in Bhopal, and later got killed in an encounter on the outskirts of Bhopal, India. Photo: UNI