The Rajya Sabha passed amendments to Finance Bill 2017, and the Lok Sabha promptly rejected it under Article 109. Finance Minister Jaitley however frets over the intrusive Upper House

~Parsa Venkateshwar Rao Jr

He generally maintains his cool. But of late, he is an agitated man. He vents his anger through the constitutional argument that an indirectly elected Rajya Sabha should not have the right to sabotage rightful legislation passed by the directly elected Lok Sabha. It is a view that he has been airing at public fora for nearly three years now. There is, of course, the irony that Finance Minister Arun Jaitley has always been a member of the Rajya Sabha and never of the Lok Sabha. But he does not allow that embarrassing fact to come in the way. He is keen to push in legislation that will reflect well on the Modi government, legislation that will leave the BJP’s stamp on governance.

Finance Bill, 2017, contained provisions for encouraging digital transactions and even penalising what this government believes to be excessive cash transactions. He defends the electoral bonds to make political funding transparent being included in the Finance Bill, and for downsizing the umpteen tribunals which are not always fully engaged but which cost the exchequer a great deal. So, he includes the merging of tribunals in the Finance Bill. The opposition nitpicks, but that is its job.

Jaitley need not have worried. It is not necessary for the Rajya Sabha to pass the Finance Bill. If it does not pass it and returns it in 14 days, it is deemed to have been passed. That is laid out in Article 109 of the constitution. So, the amendments introduced by Congress’ Digvijaya Singh and Communist Party of India (Marxist (CPI-M’s) Sitaram Yechury remained mere irritants. They were rejected by the Lok Sabha under Article 109.

But there is a hitch here. A Finance Bill is not the same as a Money Bill. A Money Bill will go back to the Lok Sabha in two weeks’ time and it does not matter if the Rajya Sabha fails to discuss and pass it. The amendments that the Upper House makes to the Bill need not accepted by the Lok Sabha even if passed by the Rajya Sabha. But the finance minister as Leader of the Upper House seemed to have felt the sting that he was unable to get through the Bill as it was passed in the Lok Sabha in a House where he is the leader. Jaitley knows that he is on strong ground. The precedents are in his favour.

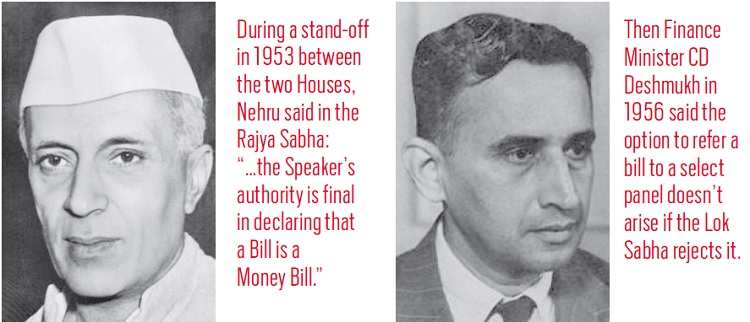

A new compendium which highlights the practices and conventions of the Council of States—Rajya Sabha At Work by VS Rama Devi, BG Gujar (Third Edition, Edited by Shumsher K Sheriff, 2016)—cites that when there was a stand-off in 1953 between the two Houses with regard to the Indian Income-Tax (Amendment) Bill, 1952, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru said in the Rajya Sabha: “…the Speaker’s authority is final in declaring that a Bill is a Money Bill. When a Speaker gives his certificate to this effect, this cannot be challenged. The Speaker has no obligation to consult anyone in coming to a decision or in giving his certificate.”

The finance minister was also on safe ground for two reasons. Finance Bill, 2017, has been certified a Money Bill by the Lok Sabha Speaker and it is a Money Bill as defined in Article 110 of the constitution. There is also a Financial Bill, defined in Article 117. It provides for imposing of taxes as specified in Article 110, and like the Money Bill, it cannot be introduced in the Upper House and requires the recommendation of the President. Finance Bill, 2017, carried the requisite recommendation of the President. Part of Article 117 (1) reads as: “…no recommendation shall be required under this clause for the moving of an amendment making provision for the reduction or abolition of any tax.”

One reason the Opposition in RS feels slighted is because Jaitley and the government packed in too many changes into the Money Bill

The flexibility available to the Rajya Sabha in the case of a Financial Bill is lucidly explained in Rajya Sabha At Work: “…not being Money Bills…the Rajya Sabha has full power to reject or amend such Bills as it has in the case of non-Financial Bills.”

Another provision available to a Financial Bill in both the Houses is: “A Money Bill cannot be a referred to a Joint Committee of the Houses. However, there is no such bar in respect of a Financial Bill.” A member of the Rajya Sabha wanted to move an amendment for referring the Life Insurance Corporation Bill, 1956, to a Select Committee. Then Finance Minister CD Deshmukh raised a point of order saying that the option was considered in the Lok Sabha but it was rejected because it was a Financial Bill as under Article 110. “A member submitted that Article 110 of the Constitution did not say that a Financial Bill could not be referred to a Joint Committee. He would even say that the Constitution did not say that even a Money Bill as such should not be referred to a Joint Committee. So far as Financial Bills were concerned, the powers of both the Houses were the same, except that they must be introduced in the other House. The Council has a right as far as Financial Bills were concerned to disagree with the recommendations of the Lok Sabha and if there was disagreement a joint sitting could be held.”

One reason the Opposition in RS feels slighted is the fact that Jaitley and the Modi government are packing in too many changes into the Money Bill so that Upper House members can merely criticise them but can’t make changes. If it were a Finance Bill, it would have been possible for the Opposition to stall it. Jaitley’s attempt to outflank the Opposition in legislation by including changes like electoral bonds as part of the Money Bill is being seen for what it is: constitutional and political circumvention.

It appears that the finance minister and the Modi government are not willing to wait till the summer of 2018 when the numbers will favour the ruling party in the Rajya Sabha. Here is a prime minister and a finance minister who seem to be in a hurry to implement what they believe to be the positive agenda of the government. The Opposition, naturally, does not share the optimism and wants to use whatever parliamentary ruses are available to create road blocks. It is a political tussle with all its ruthless, and even cynical, stratagems.