The UK government’s exercise to have a public consultation on caste has stirred a hornet’s nest. Even in such a developed country, this is an emotive and ugly issue

By Sajeda Momin in London

Theresa May’s government stirred a hornet’s nest in September when it announced that it intended to undertake a full public consultation on caste discrimination in the UK. The Hindu diaspora of just under a million has been thrown into a tizzy, with the upper castes insisting that there is no need for such an exercise as caste is not a factor in British society. However, those belonging to lower castes say that caste discrimination is a reality they face, mainly within the Indian community.

Though the government is yet to lay out the modalities of the consultation, the issue has already raised passions and a high decibel debate is under way.

The British parliament had justified the insertion of a provision against caste discrimination in the Equality Act of 2010—which deals with other forms of discrimination—on the assumption that the caste system exists in UK’s Indian diaspora. The Act originally gave power to the minister to decide whether to implement the provision or not. However, in a landmark decision, an amendment in 2013 made implementation obligatory, but so far it has not been done. The decision to outlaw caste discrimination came after a long and hard battle fought by the International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN) and other human rights groups.

The current Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, who has been a trustee of the IDSN, had said he was aware of caste discrimination abroad but was “horrified” to “realise that caste discrimination had been exported to the UK too”.

HORRIFIC REALITY

A number of research papers carried out by the IDSN and government-commissioned researchers like the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission have documented that caste discrimination exists in various forms within diaspora communities from the Indian sub-continent. It can lead to harassment, bullying and violence in the work place, in the provision of services and in education, says a briefing paper of the IDSN.

A number of research papers carried out by the IDSN and government-commissioned researchers like the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission have documented that caste discrimination exists in various forms within diaspora communities from the Indian sub-continent. It can lead to harassment, bullying and violence in the work place, in the provision of services and in education, says a briefing paper of the IDSN.

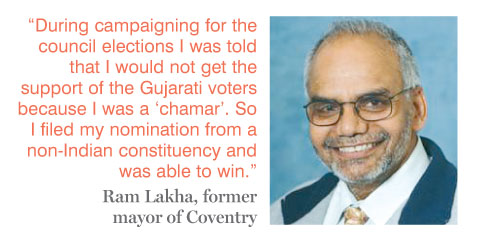

Ram Lakha, the former mayor of Coventry—a city in central England about 100 miles north of London and which has a large Gujarati population—faced discrimination in his political career because he was a Dalit. “During campaigning for the council elections I was told that I would not get the support of the Gujarati voters because I was a ‘chamar’. So I filed my nomination from a non-Indian constituency and was able to win,” said Lakha.

Ram Lakha, the former mayor of Coventry—a city in central England about 100 miles north of London and which has a large Gujarati population—faced discrimination in his political career because he was a Dalit. “During campaigning for the council elections I was told that I would not get the support of the Gujarati voters because I was a ‘chamar’. So I filed my nomination from a non-Indian constituency and was able to win,” said Lakha.

It is also customary for the local Indian community to honor each new mayor elected so as to maintain good relations with the council, but Lakha’s achievement was not recognized in the same manner because he was from a low caste. “I recently discovered from my children that they suffered difficulties at school too but they never told me. Caste feelings are there and it will take a long time for them to die out,” explained Lakha.

HARSH FORMS

As no caste-based census has been carried out in the UK, there is no exact figure of how many low caste Hindus live here, but their numbers are estimated to be in lakhs. Caste Watch UK, IDSN and other rights group say that caste discrimination is often very subtle and takes different forms. These include upper caste patients refusing appointments from doctors once they realize they are from the lower castes, health care professionals refusing to treat elderly from the Dalit community, victimization in the workplace and unfair dismissal because of caste.

The landmark Begraj & Begraj Vs Heer Manak became the first case of caste-based discrimination in the UK to be recorded in courts. In 2011, an Indian couple told an employment tribunal they faced discrimination in the workplace, ironically a solicitor’s firm, and were unfairly dismissed because they were from different castes. Vijay Begraj and his wife, Amardeep, met when working at Heer Manak, the solicitor’s firm, in Coventry. Amardeep, a Jat, said she was warned against marrying Vijay, a Dalit, by a senior colleague on the grounds “that people of his caste were ‘different creatures’ and his position in the firm was ‘compromised’”.

The landmark Begraj & Begraj Vs Heer Manak became the first case of caste-based discrimination in the UK to be recorded in courts. In 2011, an Indian couple told an employment tribunal they faced discrimination in the workplace, ironically a solicitor’s firm, and were unfairly dismissed because they were from different castes. Vijay Begraj and his wife, Amardeep, met when working at Heer Manak, the solicitor’s firm, in Coventry. Amardeep, a Jat, said she was warned against marrying Vijay, a Dalit, by a senior colleague on the grounds “that people of his caste were ‘different creatures’ and his position in the firm was ‘compromised’”.

Vijay claims that after the marriage, he was harassed, threatened, denied promotion and ultimately dismissed. But the case collapsed in February 2013 as the judge recused herself after a visit by police officers, and may now be subject to a retrial.

RESISTING THE MOVE

The anti-legislation lobby is led by the Alliance of Hindu Organisations, which has expressed “concerns about… the impact it may have on communities living within the UK”. More importantly, it believes that any anti-caste discrimination legislation is a direct slight on Hinduism. At a recent public debate on the Act organized by the Indian Forum on British Media at the House of Commons committee room, Satish Sharma, general secretary of the Council of Hindu Temples, said the legislation would be a “recipe for disaster”, creating friction within the Indian community.

Trupti Patel, president of the Hindu Forum of Britain, said her organization had found scant evidence of caste-discrimination. She claimed that the legislation would have the negative effect of making young people “aware of their caste for the first time, and encourage people to make unfounded complaints against their employers”.

Bob Blackman, the Conservative MP for Harrow East in London which is home to a very large number of Hindus, warned the legislation would lead to “completely unnecessary interference” and a “bureaucratic nightmare of proportion the Hindu community would not want to see”. Blackman, who is also the chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group for British Hindus, remarked that the caste legislation had generated more interest and involvement from the UK Indian community than any other issue he had ever encountered.

However, for Dalit rights groups, this is not a Hindu issue but one of basic human rights. Satpal Muman, chair of Caste Watch UK, said: “This is not about invading the religious and cultural space. It is purely targeted at discrimination in the public sphere. Caste discrimination is a human rights violation.” Even if a small section of people believed in the caste system, it would have an impact on the lives of people, he stressed and added that “victims of caste-based discrimination deserve legal clarity”.

The supporters of the legislation feel that the announcement of a consultation is just a stalling tactic at the behest of the Caste-Hindu lobby. Section 9 of the Equality Act of 2010, amended by parliament in 2013, already required the government to introduce secondary legislation to make caste an aspect of race, so why the fresh consultation, they ask. “The government may be hoping the consultation will allow them to point to popular opinion to justify them refusing to introduce legislation required of them by Parliament and the UN,” said Keith Porteous Wood, executive director of the National Secular Society. The consultation is expected to begin before the end of this month and run for 12 weeks.

Lead picture: Indian Diaspora protesting in UK against the caste-discrimination. Photo: www.oxpolicy.co.uk