Liberal democracy, as it is understood in the present day, is not just the rule of the majority, though it is that in a substantial way, but it is the rule of law. There are of course philosophical problems with this proposition.

Aristotle dwells on the issue of laws, who makes them, and whether laws should be changed or not. Most importantly, he recognises that there are good laws and bad, good constitutions and bad. But as a general rule, he believes that laws made by the many are better than a law decreed by a single virtuous man or a few good men.

The implied logic is that when laws are made by many, the passions and faults of each are cancelled out and only the good remains. It might be called a naïve argument by the wise cynics, but it makes sense. To put it in contemporary language, when the self-interests of many are involved, no one can pass a law that gives advantage to him or to his group alone. A compromise is forced upon them and the deal-making involved in arriving at a law would see to it that the interests of all are protected.

Issues Before Democracies

This slightly abstract detour brings us back to some of the concrete issues facing liberal democracies in practice. In the now classical governance triad of legislature-executive-judiciary, it appears that the judiciary is forced to intervene in order to uphold the law, not in just the sense of the letter of the law, but in terms of being just and fair. The game plays out interestingly and political power tussles become slightly more idealistic than they really are.

We will take examples from the three familiar and perhaps the prominent liberal democracies in the English-speaking world, India, the United States and the United Kingdom.

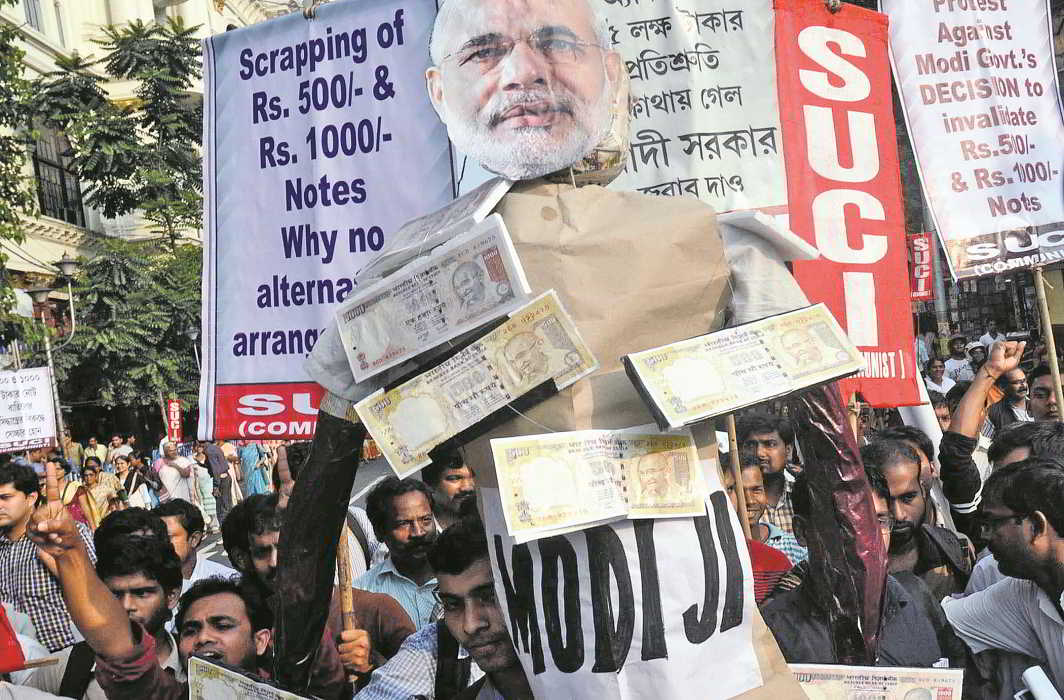

The Election Commission of India is a quasi-judicial body, and in the context of the ongoing assembly elections, directed the Reserve Bank of India to lift restrictions on cash withdrawal post-demonetisation on the contestants so that they can draw the money within the permissible limits on poll expenditure set by the commission. This was to ensure the fairness principle.

Secondly, the BJP-led NDA government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi had to issue an ordinance making the possession of Rs 1,000 and Rs 500 notes illegal—the November 8, 2016 announcement demonetising the two denominations just said that they ceased to be legal tender, and facilitated their exchange for other valid denominations. For whatever reasons, the government seemed to have felt that after giving enough time for the demonetised notes to be returned, there was need to declare their possession illegal. This was done through an ordinance.

PARLIAMENTARY APPROVAL

Once an ordinance is issued, it has to go before the legislature and made into a law. The first phase of demonetisation was an executive decision, and whatever its constitutional propriety or lack of it, the government could escape the necessity of parliament’s seal of approval. But it has to before parliament. There will not be a problem in turning the ordinance into law because it is a fait accompli of sorts.

In the United States, the newly sworn-in President Donald Trump has issued executive orders regarding vetting immigrants. But he has to go before the Congress—comprising the House of Representatives and the Senate—and get it approved. But the president’s executive order has been challenged in the New York Federal Court, which is something new.

Generally, in the American system, judicial review meant looking at the laws passed by the federal and state legislatures. The president’s executive order is not, strictly speaking, a law though it has the authority of law when it is enforced. The court intervened when the executive order was enforced in the case of two Iraqis.

In our last example—the United Kingdom, where there is no concept or tradition of judicial review because in England/Great Britain—parliament is the sovereign, and it can pass any law. But the newly formed Supreme Court—a result of Tony Blair’s constitutional reforms—the Privy Council which was part of the House of Lords has been made into an independent entity.

The Supreme Court ruled on January 24 that the British government must get parliamentary approval before activating Article 50 of the European Union treaty in order to pull the country out of the EU. The Cameron government has passed a law for holding the referendum about deciding on Brexit.

The court said that the executive cannot pull out of an international treaty though there is no constitutional provision for parliamentary ratification of international treaties, which is necessary in the United States. In India too, there is no need for parliamentary approval of international treaties. But the Supreme Court has rightly referred to the fact that the UK pulling out of EU would affect the legal status of non-UK residents in UK by virtue of the EU treaty as well as that of the UK residents in EU countries.

The Supreme Court, in fact, is adhering to the British tradition that parliament is supreme, but it has questioned the legal competence of the executive in the matter.