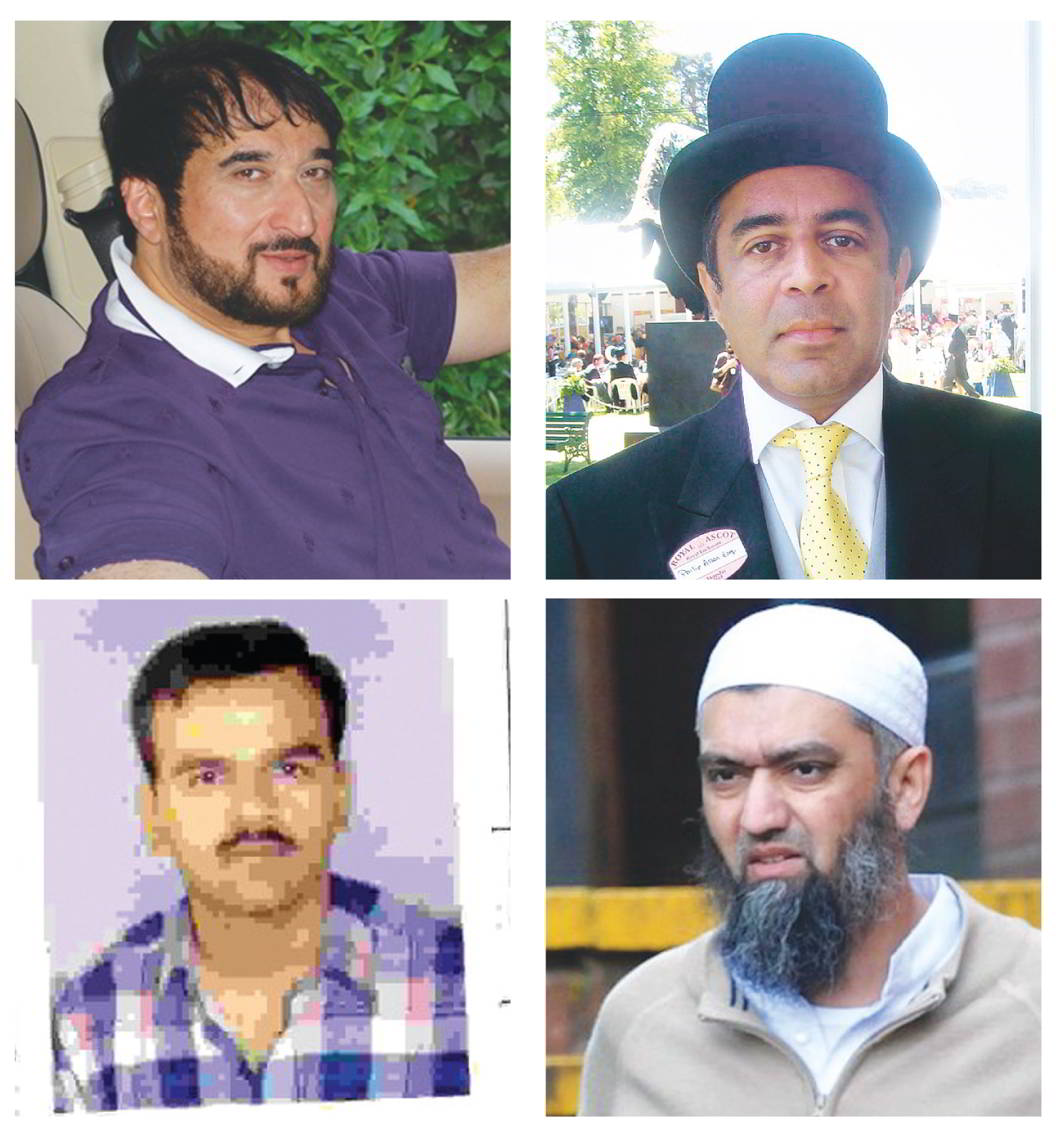

Above: Vijay Mallya at the Westminster Magistrates’ Court in London. Photo: UNI

With UK’s Serious Fraud Office wanting to conduct an independent probe into the liquor baron’s case, it could push back the possibility of his extradition even further

~By Sajeda Momin in London

The decision of Britain’s Serious Fraud Office to conduct an independent probe into liquor baron Vijay Mallya’s alleged “money laundering” may not be the boost that India is hoping for. In fact, it could push back the possibility of his extradition further. Instead of giving the UK government the “dual criminality” it needs to expedite the tycoon’s extradition to India if he is found guilty of breaking British law, he will first have to serve his sentence in the UK before he can be sent back home.

Mallya, owner of the now defunct Kingfisher Airlines, fled from India in March 2016 after defaulting on loans worth a whopping Rs 9,000 crore and sought refuge in London where he has a right of abode. Both the ED and the CBI have filed cases against him and have demanded that he be sent back to India so that he may be brought to justice. However, the flamboyant businessman has argued that the cases against him are part of a “political vendetta” and a “witch hunt”.

EXTRADITION REQUEST

The trial against Mallya was started only after the Indian High Commission in London handed over an extradition request to the British Foreign Office in January this year. It argued that India had a legitimate case and sending Mallya back was a way of showing “sensitivity towards our concerns”. Mallya was arrested by Scotland Yard on April 18 and produced at the Westminster Magistrates’ Court in central London immediately, where he was granted bail on a surety bond of Rs 5.3 crore.

Several teams of Indian agencies have since visited Britain to share evidence and coordinate with the British Crown Prosecution which is arguing the case on behalf of the Indian government. At the last hearing on September 14, Mallya’s defence team told the court they had provided a list of six experts– from the fields of airlines, banking, politics and law, including an Indian lawyer —that they intended to rely on for evidence. Condemning it as delaying tactics, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) expressed disappointment at the hard copy format in which the defence presented its documents in this age of electronics. “We received the physical box of evidence on Monday which has to be scanned and sent to India. We were disappointed to receive physical evidence in 2017. It lost us a week,” said CPS barrister Mark Summers.

Mallya’s pre-trial hearing has been set for November 20 and the final hearing will start on December 4 with the expectation it will be completed in two weeks.

The judge, Chief Magistrate Emma Louise Arbuthnot, sympathised with the CPS and also asked it if relevant evidence had been sought from India on prison conditions in the country, which she said, was a concern that had been “raised in extraditions to India before”, and by Mallya’s lawyers. Having foreseen this, the Indian authorities have already provided the CPS with photographs and emails of Mumbai’s Arthur Road jail where the absconding tycoon would be lodged if he is extradited.

DECEMBER DEADLINE

Mallya’s pre-trial hearing has been set for November 20 and the final hearing will start on December 4 with the expectation that it will be completed in two weeks. However, with courts closed for Christmas holidays, it is possible that the hearing will go into January 2018. The Indian authorities are confident of winning the case.

“Evidence presented makes out a strong prima facie case against Vijay Mallya. Despite delaying tactics, it has been possible to have an indicated date in December 2017 for the hearing and the UK counsel CPS will continue to work towards an expeditious hearing of the entire case,” said the Indian High Commission in a statement.

The extradition treaty between India and the UK came into being in 1993 but India’s track record of bringing absconders back is very poor. In fact, from a list of about 60 of India’s most wanted fugitives, only one has been extradited. Samirbhai Vinubhai Patel was wanted for burning alive 23 Muslims in Ode village during the Gujarat riots of 2002. Unlike other absconders, Patel did not fight his extradition, making it easier for the British government to take a decision. Patel was sent back in October 2016 and is currently in a jail in Anand.

But in the case of all the others—Lalit Modi, former IPL chairman, Ravi Shankaran, accused of stealing sensitive documents from the Indian Naval War Room, musician Nadeem Saifi accused in the Gulshan Kumar murder or Tiger Hanif, Dawood Ibrahim’s aide and wanted for the 1993 Gujarat blasts and who had fled to the UK—the prospects of them being sent back are bleak.

The level of proof required in British courts is very high and even Indian authorities accept, albeit off the record, that the investigating agencies don’t do their jobs properly. Shoddy proof just does not pass muster in international forums. More often, the cases are politically motivated and the defence lawyers make the point that their clients are being singled out for persecution. The judge must also be satisfied that they will get a fair trial if sent back. Also, lawyers are able to point to long drawn out trials and even fake encounters which take place in India as a matter of routine as part of their defence.

In some cases, political favouritism makes the Indian authorities extremely tardy in even applying for extradition as in the case of Lalit Modi. In March this year, the fallen cricket tzar was able to declare himself innocent simply because Indian authorities couldn’t even get Interpol to issue a Red Corner Notice against him. After misappropriating hundreds of crores by selling television rights during T20 cricket tournaments, Modi used his connections with foreign minister Sushma Swaraj and Rajasthan chief minister Vasundhara Raje to live comfortably in the UK and travel around the world like a free man despite being wanted in India.

DUAL CRIMINALITY

Extradition rules in the UK follow the dual criminality procedure where an action has to be an offence in both countries. The Indian government argues that the SFO’s investigation into Mallya’s case will establish this “dual criminality” and therefore strengthen the demand for his extradition. Mallya is accused of cheating public banks in India and subsequently laundering the money to the UK and beyond through a complex web of shell companies. “India has provided ample evidence on how Mallya used his companies/associates to invest in Britain from the money he cheated in India and how Britain’s soil has been used to further launder money to other countries,” said an Indian official. However, this has to be proved a “crime” in the eyes of British law as well.

The Extradition Treaty between India and the UK came into being in 1993 but India’s track record at bringing absconders back is very poor.

If, however, the SFO pursues the probe and decides to prosecute Mallya in a UK court, then India can kiss goodbye to getting the former playboy back. According to existing rules, the requested country will only allow extradition when there are no pending cases against him in their courts. If there is, then the case first needs to be disposed and if convicted, the person needs to serve out his sentence before he can be extradited. Hence, the SFO’s probe is a double-edged sword for India.

Even if the Mallya case doesn’t go down this path, the current battle for extradition is a long drawn out one that could last anything between 18 months to two years.

If Mallya loses at the magistrate’s level, he still has two or three higher levels of the judiciary to appeal to. If he fails to win even at the topmost Supreme Court, then he can still appeal to the British Home Secretary who would make the final decision which would definitely be a political one.

So, the good times may still last for Mallya.