As China attempts to take on the mantle of a superpower, its ambitions could be stymied by its belligerent neighbour whose nuclear tests are threatening the US and other nations

~By Colonel R Hariharan

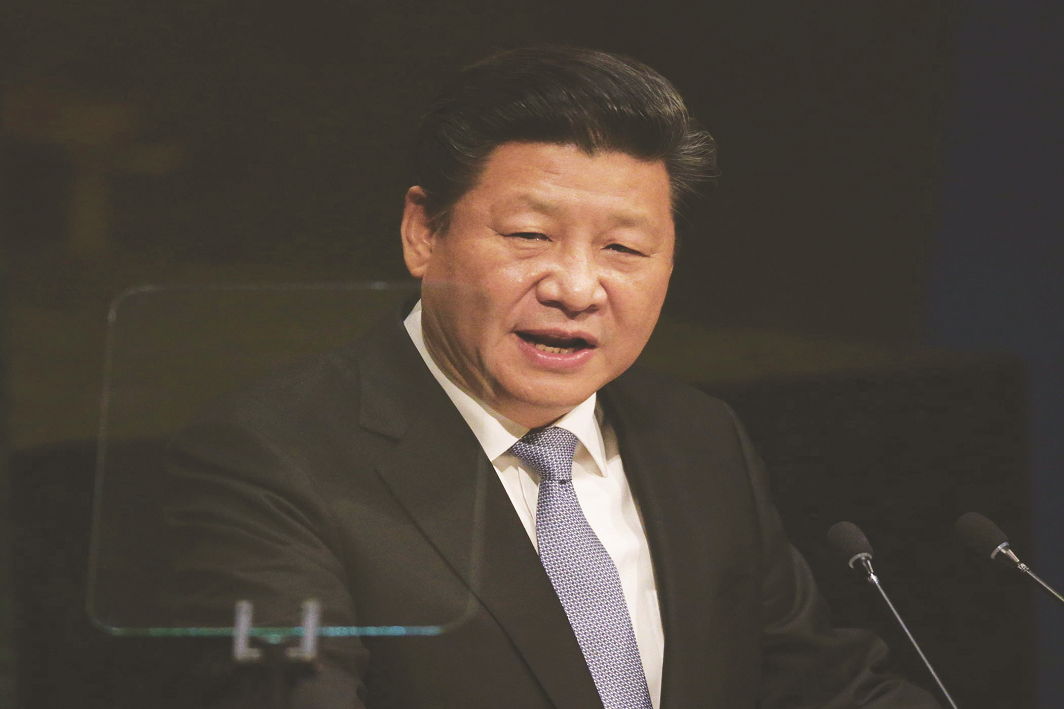

On September 3, 2017, when Chinese President Xi Jinping held a reception for dignitaries attending the ninth BRICS summit in Xiamen, he got a rude shock. North Korea (Democratic Republic of Korea—DPRK), under the leadership of the irascible Kim Jong-un, carried out its sixth and largest nuclear test in defiance of China’s strong opposition. This was not the first time it has happened. China had strongly opposed North Korea’s nuclear testing ever since it started it in 2006. But after Kim Jong-un came to power in 2011, North Korea’s nuclear weapon and missile development projects have made giant strides to enable him to test both nuclear devices and inter-continental ballistic missiles.

China’s prompt response to North Korea’s nuclear tests feature two operative phrases—“firm opposition” to North Korea’s conduct which was “flagrant and brazen violation of international opinion”. That may not be sufficient any more as China under President Xi aspires to become a superpower in the emerging international security environment. The rapid progress in North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missile capabilities is a testimony to the dynamics of change.

Though President Xi did not immediately respond to the September 3 blast, he was probably not amused.

CHANGE IN STANCE

After meeting Russian President Vladimir Putin in Beijing, Xi said China was committed to the goal of North Korea giving up its nuclear weapons. The statement is significant as it shows China’s recognition of the need for international collective action to stop North Korea’s nuclear capability. So it was not surprising that China did not oppose important sections of the US draft resolution brought before the UN Security Council in the wake of the September 3 test.

This is a change in China’s stand when UNSC sanctions on North Korea were passed in 2006 and 2013. The reasons for China’s opposition to North Korea acquiring nuclear capability are strategic. North Korea acts as the strategic vanguard to China not only in North Asia but also in the “China Seas” region, where the US flexes its military muscle regularly. Nuclearisation of North Korea would give the US an opportunity to introduce nuclear weapons in South Korea, its strategic partner. This could thwart China’s desire to neutralise US domination of the region. Already, North Korea’s repeated missile testing has enabled the US to introduce the THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defence) anti-missile system in South Korea. To a certain extent, it cramps China’s missile capability. So China cannot afford to provide the US and its allies further opportunity to enlarge its capability.

The North Korean nuclear test was undoubtedly a loss of face for China and President Xi. The BRICS summit was part of his slew of global initiatives to create a new world order as an alternative to the US and western domination of the world. President Xi’s other initiatives—the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and One Belt One Road—also aim at increasing China’s strategic reach and influence across Asia, Africa and Europe.

Peaceful development is central to Xi’s marketing pitch for all these international initiatives.

After US President Donald Trump has chosen to renege on many of the US’ international initiatives already undertaken, including the UN Paris agreement on Climate Change, UNESCO, the Trans-Pacific Partnership and probably WTO as well, President Xi has shown his readiness to take on the leadership role. For the success of these strategic initiatives, China requires a peaceful environment, which could be jeopardised by Kim Jong-un’s belligerence.

CONSOLIDATING POWER

Internally also, the North Korean nuclear test comes at an inconvenient time for Xi. He had been working hard for the last four years to consolidate power within the ruling hierarchy of the Communist Party of China (CPC), the government and the PLA. His sustained anti-corruption drive has enabled him to carry out a “house cleaning” drive to weed out potential contenders to power from the CPC and the PLA.

Media reports indicate that the Congress is also likely to anoint Xi as a mentor in the CPC constitution, a rare honour bestowed so far only on Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. Speculation is rife that the Congress might nominate him as chairman of the CPC for life, the first step to becoming a lifetime president. Under these circumstances, he cannot afford to be seen as a weak and ineffective leader who cannot rein in North Korea’s brazen conduct.

Ever since North Korean strongman Kim Jong-un succeeded his father, Kim Jong-II, in 2011 as supreme leader, he has relentlessly pursued his ambition to acquire indigenous nuclear and missile capability. After the sixth nuclear test, North Korea seems to have developed the capability to produce hydrogen bombs. North Korea has steadily upgraded its missile capability. This year alone, it carried out 17 missile tests of varying ranges and capabilities. Two of the missiles have been fired over Japan. At least two of the missiles tested can be classified as inter-continental ones, capable of carrying a nuclear warhead. This would indicate that North Korea is well on its way to achieving its over-ambitious goal of developing a missile capable of hitting the US.

RASH COMMENTS

Donald Trump, perhaps the most unpredictable US President ever, and his DPRK counterpart have been bad-mouthing each other and exchanging insults over social media. It was set off after Trump, in his inimitable style of making rash statements, threatened to “totally destroy” North Korea while addressing the UN General Assembly last month. Kim, equally ebullient, took the name-calling to a new low, calling Trump “a rogue and a gangster fond of playing with fire, rather than a politician”. Kim concluded his statement with a promise to “surely and definitely tame the mentally deranged US dotard with fire”, and finally called Trump “an old person, especially one who has become weak or senile”.

Though the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov likened the slanging match between the two leaders to kindergarten fighting, the dangers of an unprecedented war exploding in and around the Korean peninsula are more real now than ever before.

In a statement on October 7, Kim Jong-un said nuclear weapons were a “powerful deterrent firmly safe-guarding the peace and security in the Korean peninsula and Northeast Asia in the face of protracted nuclear threats of the US imperialists”. This is indicative of his insecure and paranoid mindset. Given this background, North Korea’s repeated threats to strike US bases in Guam and warnings to South Korea and Australia for participating in military drills organised by the US, cannot be taken lightly.

So it is not surprising that not only South Korea, Japan and China, but countries in the neighbourhood such as Australia, are worried about an outbreak of war in case Kim goes berserk.

The latest North Korean nuke test represents a watershed moment in China’s relations with its Korean ally, a relationship that has been cultivated during the last five decades. In the heyday of their relationship, Mao described it as “close as the lip and teeth”.

OLD TIES

The relationship, cemented by the sacrifice of 1,80,000 Chinese soldiers’ lives who fought to save North Korea from being overrun by US and UN troops during the Korean War in the past, had suffered periodic hiccups due to differences on ideological, political and trade issues. In the 1960s, Mao’s Cultural Revolution caused serious ripples in relations with Kim Il-sung who considered it an incorrect implementation of the principles of Marxism-Leninism.

The drift in China-North Korea relations started when Deng advocated political and economic pragmatism and opened China to the world. The Kim dynasty did not take it lightly; it has ruled North Korea with a hard fist, though there were brief periods of honeymoon in relations with China. After Kim came to power, he ordered the execution of his uncle, Jang Song-thaek, considered close to China, for plotting a coup. Similarly, he is believed to be behind the murder of his brother, Kim Jong-nam, who was living in exile in Macau under Chinese protection. These instances indicate Kim’s paranoia about China attempting a regime change. But China may not want to do that as it could trigger an era of instability in a country geographically too close for its comfort.

It seems there is no other option for the US and China but to set aside their strategic differences and come together to defang North Korea. Is it possible? How will they do it without triggering a war? That is a million-dollar question for security pundits.

The writer is a retired military intelligence specialist on South Asia

and is associated with the Chennai Centre for China Studies

and the International Law and Strategic Studies Institute