Though the US President’s Executive Order seems to violate the constitution which says that one cannot discriminate on the basis of nationality or place of origin, it has been drafted cleverly to evade a clash with the statute

~By Sujit Bhar

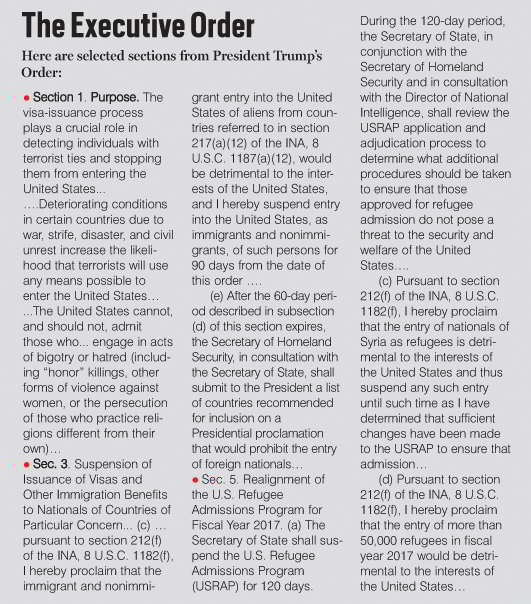

President Trump’s Executive Order on the visa ban has triggered outrage and chaos in equal measure. Specifically, it bars entry into the US of all refugees for 120 days; bars citizens (even non-refugees) of Iraq, Iran, Syria, Somalia, Sudan, Libya and Yemen for 90 days and bars Syrian refugees indefinitely.

Even as millions of refugees, students, green card holders and immigrants with permanent residency remain in limbo, legal and constitutional challenges to the ban are mounting, apart from the spontaneous protests that have erupted across America.

ACLU LAWSUIT

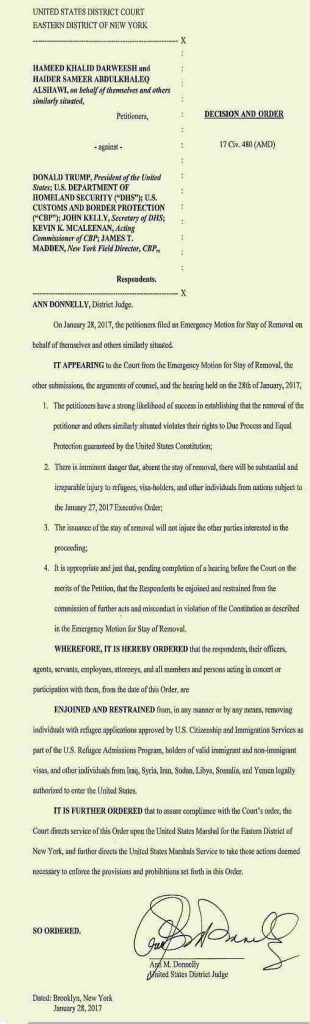

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the largest pressure group in the US with over 7,50,000 members, and other activist groups filed a class action lawsuit seeking to challenge the President’s order. The temporary restraining order was achieved. Lee Gelernt, deputy director of ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project, said in a statement: “This ruling preserves the status quo and ensures that people who have been granted permission to be in this country are not illegally removed off US soil.”

A US district court judge in Brooklyn ruled to halt the enforcement of Trump’s Executive Order (See Box) the day after he signed it. At least four other state courts have done the same. The essence of the New York judge’s order on the petition by Hameed Khalid Darweesh and Haider Sameer Abdulkhaleq Alshawi is as follows: “IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that the respondents (who include Donald Trump, President of the United States)….are enjoined and restrained from… removing individuals with refugee applications approved by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services as part of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, holders of valid immigrant and non-immigrant visas, and other individuals from Iraq, Syria, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen legally authorized to enter the United States.”

Against this backdrop, experts have been looking into the credibility of the Executive Order and trying to decide how legally binding it could be or whether it could even be anti-constitutional. Steven Mulroy, a law professor in constitutional law, criminal law and election law at the University of Memphis, has written in the theconversation.com that deciding whether it’s legal or not is “a surprisingly tricky question”.

There are several aspects to this Order that need extreme scrutiny. The sheer ethical and humanitarian angle apart, the first question is whether this Order finds any footing at all in the legal world. It originated in Trump’s election campaign rhetoric when he declared that he wanted to impose a temporary ban on the entry of all Muslims into the country.

Immigration Acts

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 says:

“Whenever the President finds that the entry of any aliens or of any class of aliens into the United States would be detrimental to the interests of the United States, he may by proclamation, and for such period as he shall deem necessary, suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrants or non-immigrants, or impose on the entry of aliens any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate.

Whenever the Attorney General finds that a commercial airline has failed to comply with regulations of the Attorney General relating to requirements of airlines for the detection of fraudulent documents used by passengers traveling to the United States (including the training of personnel in such detection), the Attorney General may suspend the entry of some or all aliens transported to the United States by such airline.”

The Immigration Act of 1965, which amends the 1952 Act, says:

“Except as specifically provided in paragraph (2) and in sections 1101(a)(27), 1151(b)(2)(A)(i), and1153 of this title, no person shall receive any preference or priority or be discriminated against in the issuance of an immigrant visa because of the person’s race, sex, nationality, place of birth, or place of residence.”

CLEVER DRAFTING

Now that it is an Executive Order, a closer scrutiny shows that it has been drafted very cleverly. While it bars entry of refugees and even visa holders from seven Muslim countries, it does not mention “Muslims” specifically. That is how the Order, possibly, evades a clash with the US constitution. Mulroy writes: “In explaining why those seven countries were chosen, the order itself cites the (Barack) Obama-era law stating that persons who in recent years have visited one of these seven terrorism-prone nations would not be eligible under a ‘visa waiver’ program.” That is where the sleight of hand has happened.

Mulroy adds that “the defining characteristic here is terrorist danger, not religion. That’s why only seven of more than 40 majority Muslim countries are affected.” The Obama-era rule, he says, isn’t based on nationality, but rather on whether someone of any nationality visited the danger zone since 2011—a criterion not outlawed by the 1965 statute. But taking a leaf out an Obama action and using it to his own benefit was certainly a wily move by Trump.

OTHER VIOLATIONS

The order arguably violates both a federal statute and one or more sections of the constitution—depending on whether the immigrant is already in the US, according to Mulroy. He says that “in the end, opponents’ best hope for undoing the order might rest on the separation of church and state”.

Another legal expert, David Bier wrote in cato.org that the Immigration Act of 1965, which replaced an earlier 1952 statute, clearly prohibits discrimination in the issuance of an immigrant visa based on national origin. (See box). Bier, incidentally, is an immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute’s Center for Global Liberty and Prosperity. He is an expert on visa reform, border security, and interior enforcement. He says that Trump may have used the earlier executive order out of context and, then part of the 1952 statute (8 U.S.C. 1182(f), 1952), also out of context, and mixed them to form a humongously explosive order.

How does the order violate the statute? The 1965 amendment is clear in saying: “…no person shall receive any preference or priority or be discriminated against in the issuance of an immigrant visa because of the person’s race, sex, nationality, place of birth, or place of residence.” The earlier one, though, deals with a Presidential order, which lays out that the President can deny entry, to “any class of aliens if he finds” that such entry “would be detrimental to the interests of the United States”. Here, Bier cuts a prevalent argument that “this (earlier) provision allows President Trump to simply ignore the ban on discriminating based on national origin”. He adds: “But a basic rule of statutory construction holds that in the case of a conflict, the statute enacted most recently wins. In this case, that would be the 1965 amendments banning discrimination in the 1952 Act.”

LAW DISTORTED

Jonathan Turley, Constitutional Attorney, George Washington University, in an interview in PBS Newshour goes deeper into the issue. He said: “There’s no question that the law says that you cannot discriminate on the basis of nationality or place of origin. And that certainly helps the challengers. But like much else in this debate, much of that law has been distorted. It only takes you so far. First of all, the law doesn’t apply to refugees. It applies to immigrants. It’s used when you have visa issues. Also, it doesn’t cover religious discrimination. Also, in 1990, the act was amended to exclude procedural changes as a form of discrimination. And that reduces the use of the 1965 law, I think, as a serious challenge. And also it means that much of that order, as they challenge, doesn’t fall under the law.”

That confuses matters further. Mulroy reveals another pitfall, saying that if due process issues are not considered “the order arguably violates both a federal statute and one or more sections of the constitution – depending on whether the immigrant is already in the US”.

The recent court orders halting enforcement of the Trump order relied on a legal argument that it violated due process or equal protection under the constitution. Due process means that people get procedural safeguards–like advance notice, a hearing before a neutral decision-maker and a chance to tell their side of the story–before the government takes away their liberty. Equal protection means the government must treat people equally, and can’t discriminate on the basis of race, alien status, nationality, and other irrelevant factors.

Mulroy adds: “The Supreme Court has said that even immigrants who are not citizens or green card holders have due process and equal protection rights, if – and only if – they are physically here in the US. That’s why the recent court orders on due process and equal protection help only individuals who were in the States at the time the court ruled.” That clears the case of separation of the church and state, too, because reference in the constitution incorporates due process.

Clearly, the legal challenges will be like entering a minefield. It will be a bloody and lengthy battle, which means that millions of unfortunate families and individuals will be trapped in a hell of one man’s making.

—With Special reports from the US

Lead picture: President Trump’s Executive Order on the visa ban has triggered outrage and chaos in equal measure. Photo: UNI