It is a mind-blowing legal battle for many unobvious reasons. First, it is a battle between two big, high-profile universities— the University of California (Berkeley) and the Broad Institute at Massachusetts Institute of Technology of Harvard University. It is a patent battle, which means it is about who got there first and who can assert the intellectual property right.

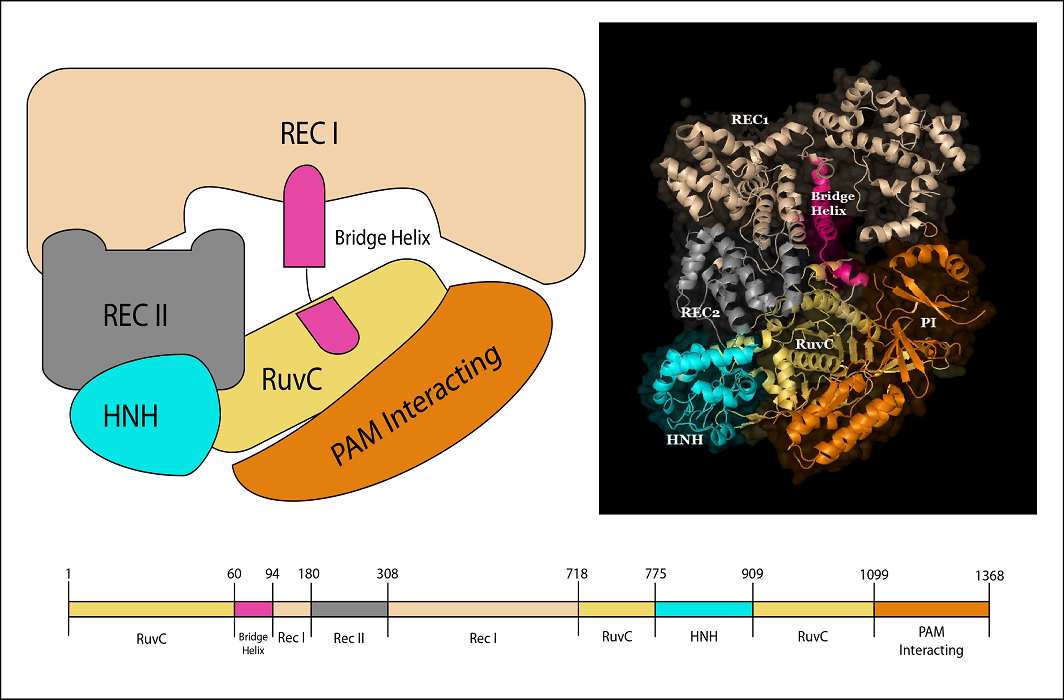

The technology at issue is that of using a protein —CRISPR-Cas9—to slice DNA, which is part of the burgeoning medical research field of genetic therapeutics, with huge commercial implications and millions of dollars in earnings for anyone who owns the patent.

The United States Patent Trial and Appeal Board, in its decision on February 15, 2017, said that Broad Institute patents do not clash with the use of the gene-splicing method through CRISPR-Cas9, mastered by the University of Berkeley. It is a case that would puzzle scientific as well as legal minds, and the judges at the US Patent Trial and Appeals Board were really faced with an intellectual challenge.

Is this one of those ideal cases in which the technologically and economically advanced United States has created an intellectual benchmark? Many in India, the intelligentsia, the intellectuals, and the scientists are not very enamoured with patents. Call it the civilisational bias. The argument is that knowledge, including discoveries, should not be turned into private property because knowledge is universal. It is a common sentiment not just in India but in other places as well. Remember the inventor of the World Wide Web (www), Sir Timothy John Berners-Lee, did not patent his invention, which he could have. At home, we have the case of Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose, who discovered radio messaging and gave a public demonstration of it in Kolkata in 1895, though he never patented it, and Guglielmo Marconi, who mastered it two years later patented it.

The argument that it would be a waste of resources for several institutes to be racing each other in the same field will remain a timid response

In its order, the US Patent Trial and Appeals Board did what it could, slicing through the technicalities— scientific as well as legal—that lay on the way. Reading the order, one finds that the evidence presented by the experts from both sides has been weighed, though one cannot say evenly. The issue at stake was this: though UC (Berkeley) was the earlier one to have used the CRISPR-Cas9 method for gene-splicing, its discovery did not imply that when Broad Institute used it for a different purpose, it was treading on the feet of the UC (Berkeley) group. The moot issue in a patent battle is who did it first.

Broad argued, and the board accepted, that UC (Berkeley) had used CRISPR-Cas9 in prokaryotic cells—that is simple unicellular organisms like the bacteria which did not have complicated or differentiated inner structures, whereas Broad had applied the method in eukaryotic cells—evolved cell structures which had a nucleus separated by a membrane from the other parts of the cellular organism, and this includes plant and animal cells. UC (Berkeley) argued that its method, CRISPR-Cas9 – implied that it could be extended and used successfully in other organisms too.

The board, going through the evidence offered by the experts, came to the conclusion that UC (Berkeley)’s method promised the prospect of its future use in other organisms, but it did not assure success. A patent can be offered only when the method or technology is perfected and a skillful practitioner can use it with the confidence that it will work. The assurance of success was not there in the earlier claims made for UC (Berkeley)’s breakthrough.

While denying that all the possible future uses of CRISPR-Cas9 gave UC (Berkeley) patent rights because there was no guarantee of success when applied to other organisms—in this case eukaryotic cells—the board did not award the patent to Broad Institute.

In its summary, the board says, “Broad has persuaded us that the parties claim patentably distinct subject matter, rebutting the presumption created by declaration of this interference. Broad provided sufficient evidence to show that its claim, which are all limited to CRISPR-Cas9 systems in a eukaryotic environment, are not drawn to the same invention as UC’s claims, which are all directed to CRISPR-Cas9 systems not restricted to any environment. Specifically, the evidence shows that the invention of such systems in eukaryotic cells would not have been obvious over the invention of CRISPR-Cas9 systems in any environment, including in prokaryotic cells or in vitro, because one of ordinary skill in the art would not have reasonable expected a CRISPR-Cas9 system to be successful in a eukaryotic environment. This evidence shows that the parties’ claims do not interfere. Accordingly, we terminate the interference.”

UC (Berkeley) said that it respects the decision but it would want to consider the option of approaching a federal court in the matter. Meanwhile, Broad Institute, has indicated that there is room for many patents in the field and that it was not a case of a single patent covering the whole, wide field of gene splicing. Here is a case which involves the legality of scientific developments in the context of intellectual property rights, and it requires that scientific workings qua science have to be understood as well.

It would be interesting to see whether Indian scientists and research centres would want to fight patent battles with each other for the sake of the market pie, or will the country continue with the Soviet model where research work done in an institute will not be replicated by another?

It will also be necessary that India develop a strong patent regime and a patent dispute resolution mechanism. It may also be necessary that Indian universities and research centres would have to learn to compete with each other. The argument that it would be a waste of resources for several institutes to be racing each other in the same field will remain a timid response.