The Bombay High Court bench of Justices BP Colabawalla and Firdosh Pooniwalla on September 18 pulled up the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) for its delay in granting certification to the film Emergency. On September 4, the Court had ordered the CBFC to consider objections from the Jabalpur Sikh Sangat and others and take a decision on releasing the film’s certificate by September 18, 2024. The Court found that the CBFC effectively issued a certificate for the film despite the chairperson’s signature being pending and added that the Court could not direct the CBFC to release the certificate without considering these objections as it would breach of the Madhya Pradesh High Court order.

The film has faced controversy, with objections from the Jabalpur Sikh Sangat and others. The Madhya Pradesh High Court had directed the CBFC to consider these objections before certifying the film.

The Bombay High Court observed that once the filmmakers complied with the CBFC requirements and the CD was sealed, the CBFC applied its mind and effectively issued the certificate.

However, on September 18, the Bombay High Court found that the CBFC hadn’t met the deadline given by it, citing that the matter had been referred to the Revising Committee under Rule 25 of the Cinematograph (Certification) Rules, 2024. The High Court has now extended the deadline to September 25, 2024, directing the Revising Committee to decide on the certificate and communicate its decision to the court.

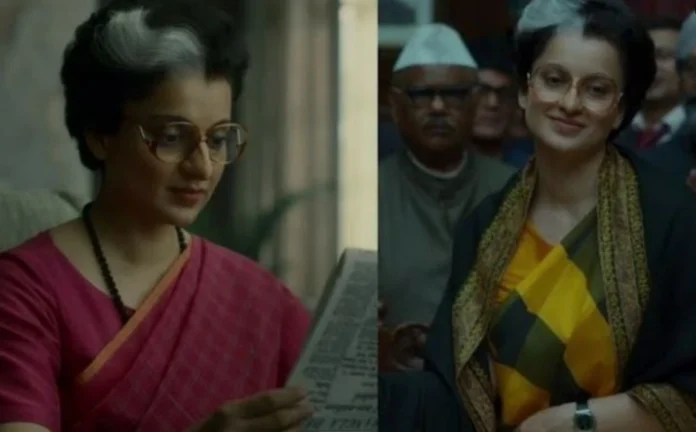

The movie is a biographical political drama film directed by Kangana Ranaut, who also plays the role of former prime minister Indira Gandhi. The film has been facing controversy, with some groups demanding a ban due to its depiction of certain events and figures. The CBFC’s delay in certifying the film has sparked a debate, with some questioning whether the ruling party is trying to block the film’s release ahead of the assembly elections in Haryana due to the fear of losing Sikh votes.

Other Bollywood films that had run-ins with the CBFC and reached courts include:

Udta Punjab (2016): The CBFC demanded 94 cuts, including removal of references to Punjab, on June 6, 2016. Its chairperson Pahlaj Nihalani cited concerns over explicit content, drug use and negative portrayal of Punjab. Filmmakers, politicians and activists condemned CBFC’s decision, alleging censorship and political interference. Filmmakers appealed to the Bombay High Court against the CBFC’s decision on June 13, 2016. The High Court allowed the film’s release with only one cut (a scene showing a character urinating) and some disclaimers on June 13, 2016.

No Fathers in Kashmir (2018): The CBFC granted an “A” certificate with five cuts on April 11, 2018. Filmmaker Ashvin Kumar appealed to the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) against the cuts on May 2, 2018. The FCAT directed the CBFC to grant a “U/A” certificate with two modifications on July 11, 2018. The CBFC re-evaluated the film and granted a “U/A” certificate with three cuts on July 25, 2018.

Lipstick Under My Burkha (2017): The CBFC denied certification on January 23, 2017, citing the film was lady-oriented and contained sexual content. Filmmaker Prakash Jha appealed to the FCAT against the CBFC’s decision. On April 18, 2017, the FCAT directed the CBFC to grant an “A” certificate with some cuts.

War and Peace (2002): An Indian documentary film directed by Anand Patwardhan faced censorship issues with the CBFC. The Board refused certification on October 11, 2001, citing concerns over promotion of communal disharmony, anti-national sentiments and criticism of Hindu nationalism. The filmmaker appealed to the FCAT against the CBFC’s decision. The FCAT directed the CBFC to grant certification without cuts on January 15, 2002. The CBFC then challenged the FCAT’s decision in the Bombay High Court. The Court upheld FCAT’s decision, allowing the film’s release without cuts on February 22, 2002. CBFC Chair Vijay Anand cited concerns over the film’s portrayal of Hindu-Muslim violence, while on the other hand, Patwardhan argued the film promoted peace and secularism.

Final Solution (2004): The CBFC refused certification on August 5, 2003, citing concerns over communal sensitivity and potential for violence. Filmmaker Rakesh Sharma appealed to the FCAT against the CBFC’s decision. The FCAT directed the CBFC to grant certification without cuts on January 22, 2004. The CBFC challenged the FCAT’s decision in the Delhi High Court. The Court upheld FCAT’s decision, allowing the film’s release without cuts on February 26, 2004. The CBFC cited concerns over the film’s portrayal of Gujarat 2002 communal riots. However, the filmmakers argued the film promoted peace and secularism.

MSG: The Messenger (2015): The CBFC initially denied clearance, citing concerns over glorification of the director/actor, a real-life Dera Sacha Sauda sect leader, potential communal tensions and objectionable content. The film underwent multiple cuts and changes to address the CBFC concerns. The CBFC granted clearance with a “U” certificate after 40-50 cuts and modifications. The Punjab and Haryana High Court stopped the film’s release in 2015 due to concerns over law and order. Later, the Supreme Court overruled the High Court’s decision, allowing release of the film.

Gulabi Aaina (2003): Citing concerns over explicit content, homosexual themes, promoting homosexuality, the CBFC refused certification on April 24, 2003. Filmmaker Sridhar Rangayan appealed to the FCAT against the CBFC’s decision. The FCAT directed the CBFC to grant certification with cuts on August 21, 2003. The CBFC cited concerns over the film’s portrayal of transsexuals and homosexuals. Rangayan argued that the film promoted understanding and acceptance.

The Pink Mirror (2003): The CBFC refused certification on February 14, 2003. Filmmaker Sridhar Rangayan appealed to the FCAT against the CBFC’s decision. The FCAT directed the CBFC to grant certification without cuts on April 22, 2003.

Fire (1996): The CBFC granted an “A” certificate with cuts on August 22, 1996. Right-wing groups, including the Shiv Sena, objected to the film’s portrayal of lesbian relationships and Hindu mythology. There were censorship demands to remove the scenes depicting lesbian relationships and change the character’s name to avoid reference to the Hindu mythology. Filmmaker Deepa Mehta refused to make changes, citing artistic freedom. Mehta challenged CBFC’s cuts in the Bombay High Court. The High Court upheld CBFC’s decision, but allowed the film’s release with minor cuts.

Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love (1996): Citing explicit content, obscenity and promoting extramarital relationships, the CBFC refused certification on January 26, 1996. Filmmaker Mira Nair appealed to the FCAT which directed the CBFC to grant certification with cuts on March 15, 1996. The CBFC challenged the FCAT’s decision in the Bombay High Court, which upheld the FCAT’s decision, allowing the film’s release with minor cuts. The CBFC cited concerns over explicit content. In defence, Nair argued the film was artistic and educational.

Bandit Queen (1994): Initially the CBFC granted an “A” certificate with cuts on January 14, 1994. Objections were related to graphic violence, explicit language, rape scenes and nudity. Filmmaker Shekhar Kapur appealed to the FCAT against the CBFC cuts. The FCAT then directed the CBFC to grant certification with fewer cuts on February 22, 1994. The Delhi High Court upheld the FCAT’s decision in April 1994). According to the filmmaker, the film was based on true events and required authenticity.

Paanch (2003): The CBFC denied clearance to the film. The film underwent multiple cuts and changes to address the CBFC concerns which included violence and gore, explicit language and toning down mature themes. Film-maker Anurag Kashyap challenged the CBFC’s decision in court and the Bombay High Court ruled in favour of the film.

Padmaavat (2018): The CBFC granted “U/A” certificate with modifications on December 28, 2017 with objections on historical inaccuracies, glorification of Sati (self-immolation) and the potential for communal violence. Cuts and modifications were made which included changing the title to Padmaavat, removal of Ghoomar song’s objectionable content, modifications to the self-immolation scene, and added disclaimers about fictionalization. The Supreme Court stayed ban orders by Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Haryana governments. The Court ruled that CBFC’s certification is final.

—By Shivam Sharma and India Legal Bureau